Anti-Nuclear Movement

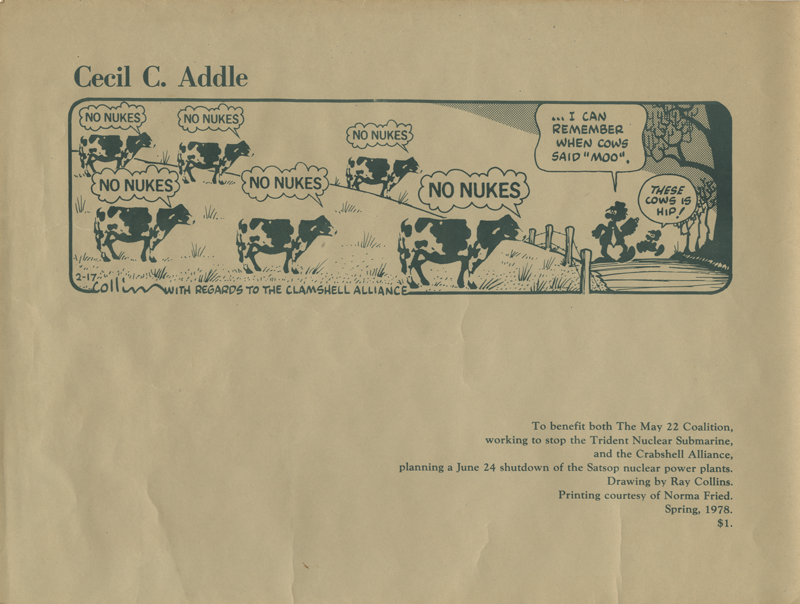

The Clamshell Alliance, which formed in 1976 as part of the antinuclear and environmental movements, utilized encampments as a primary tactic in their campaign to stop the construction of a twin-reactor nuclear energy plant near Seabrook, New Hampshire.

The following is an excerpt from a 1977 _Rolling Stones_ article, “The Clamshell Alliance Holds Nukes at Bay,” by Michael Aron.

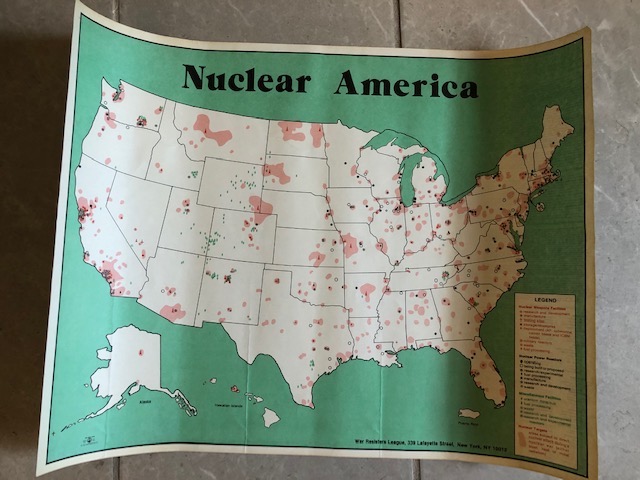

“The Clamshell is a coalition of groups that came together last year after all legal attempts to stop Seabrook had failed,” explained Anna Gyorgy [an organizer with the Clamshell Alliance]. Image via Ed Heddman, Grace Heddman, Gale Jackson and Jennifer Kraar. Published by War Resisters League, 1979.

“Gyorgy said that the coalition heard about an occupation of a nuclear site in West Germany, and activism in Denmark that forced the Danish government to cancel six nuclear plants there.

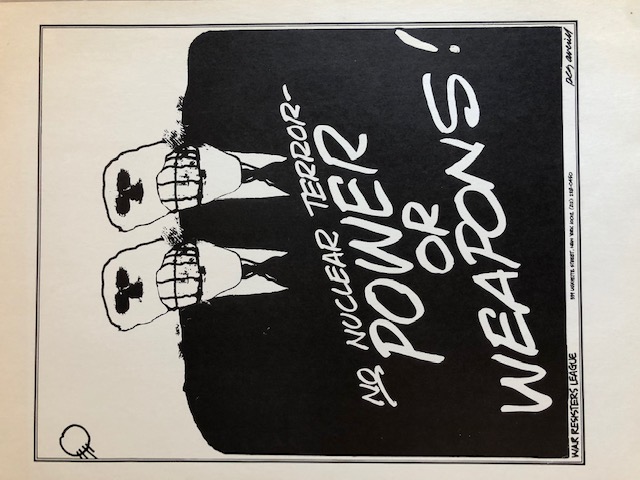

A drawing of two skeletons, both wearing suits and ties. Across their bodies are the words “No Nuclear Terror - Power or Weapons!” Image via Peg Averill, War Resisters League.

Inspired by the Europeans’ successes, the New England people began talking about direct action. In the bitter cold of January 1976 a 22-year-old apple picker named Ron Rieck camped for 36 hours in a weather tower. In April 1976 nearly 300 people walked onto the Seabrook site and spent a peaceful day there.

On August 1st, 1976 the Clamshell sent a small occupying force to the Seabrook site. Eighteen people were arrested. Three weeks later, the Clams returned. This time 180 were arrested. At an Alternative Energy Fair in October, the Clams set April 30th, 1977, as the date for the next occupation, determined to show up with 1800 people. “It’s cosmic,” said Gyorgy. “We said we would grow ten times and we did.”

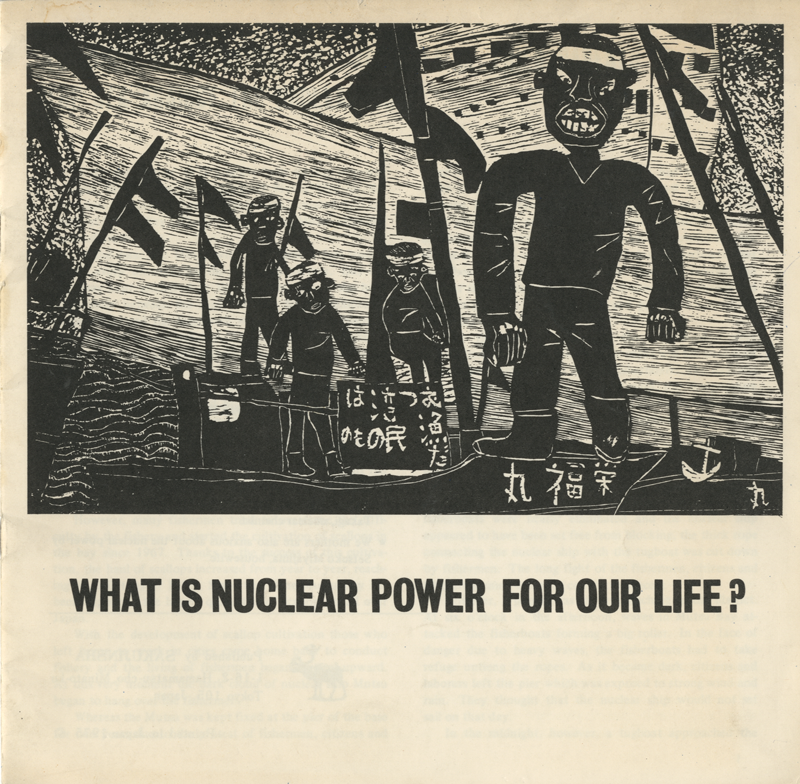

Image via Interference Archive.

Accordingly, on April 30th, no one was allowed on the Seabrook site who had not received Quaker training (or its equivalent) in nonviolent civil disobedience. Training sessions, which had begun in March, consisted of four to six hours of discussions and role playing to teach the occupiers how to resist provocation by the police, press, agitators, judges and jailers. People who came to Seabrook untrained were given a two-hour crash course on the morning of April 30th by the Movement for a New Society, a Philadelphia-based commune devoted to higher consciousness. A Clamshell publication, “The Occupier’s Handbook,” reflecting the Quaker orientation, set forth seven principles of conduct: no drugs, no alcohol, no running, no movement after dark, no weapons, no destruction and no violence. To ensure that no provocateurs infiltrated the site, participants were issued armbands and divided into “affinity groups” of ten to twenty. These affinity groups can still be put together within 24 hours.

Image via mage via Interference Archive.

On April 30th 2000 men and women came to Seabrook prepared for arrest and incarceration. Every one of them had been trained in nonviolent civil disobedience. Marching from four directions, carrying heavy backpacks, singing, yipping and hooting, they converged on the site of a proposed nuclear power plant and sat there for 23 hours. Six hundred media people had been invited; more than 400 came. In order to prevent violence, the Clamshell had informed the governor’s office and the police of its every move in advance. The Clamshell’s video crew recorded the event. On May Day the arrests began. It took state troopers from five New England states 15 hours to remove all the occupiers.“

Mauna Kea Encampment

In July 2019, following years of indigenous organizing and litigation, Hawaii’s governor’s announcement that construction of a controversial $1.4-billion telescope on a mountain sacred to Native Hawaiians was imminent.

More than 30 indigenous elders, many in their 70s and 80s, set up camp at the base of the mountain and physically blocked the road. Nearby, seven other Native Hawaiians chained themselves to a cattle guard, forming a second line of defense.

Protect Mauna Kea at Hawaii Kai and Hanauma Bay, May 31, 2015. Image via Doug Matsuoka/Flickr.

Police picked up and carried away many of the elders; some were taken away in wheelchairs while younger protesters wept and pleaded with the arresting officers.

“Law enforcement, most of them Hawaiians themselves, moved slowly and respectfully, looking pained and conflicted as they arrested the kūpuna [elders],” reported Vox.

After being cited and released, the elders returned to their seats in the road.

“This is all we have left, so we aren’t going to move,” veteran activist Walter Ritte, one of the elders arrested, told Vox. “They’re going to have to keep arresting us — and we’ll keep coming right back. The mountain represents us, all Hawaiians, so we’re not going to let them take our mountain. We aren’t going to leave her.”

In the following days, some 2,000 people joined the first wave of protesters. The encampment, which held prayer ceremonies three times a day and included a medic tent and kitchen, gained international attention.

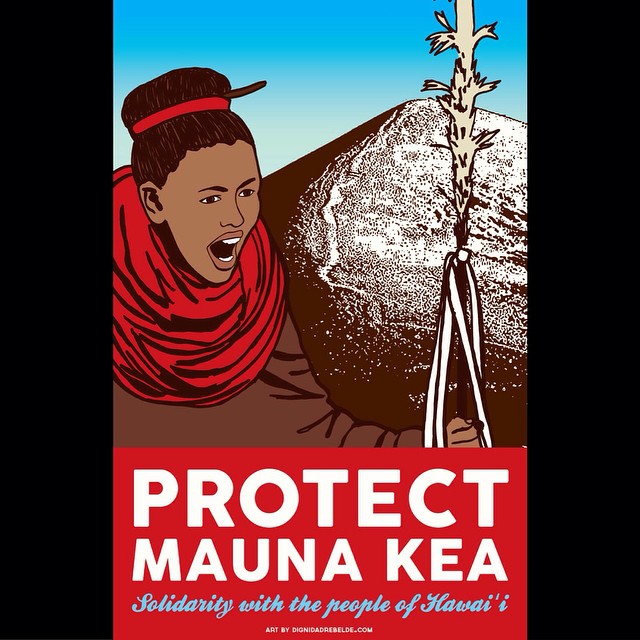

Protect Mauna Kea graphic. Image via Dignidad Rebelde/Flickr.

Opposition to the new Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) and other telescopes on Mauna Kea had been mounting for decades.

The occupation of the road prevented construction crews from building the new telescope. They also halted access to thirteen already existing telescopes. The shutdown was the longest interruption to scientific activity on Mauna Kea in the five-decade history of astronomy on the mountain, reported Nature. As such, the protests brought issues of land rights and sovereignty into the consideration of a new audience: international astronomers.

As scientists who otherwise supported the building of the TMT grew uncomfortable with their role in the desecration of a religious site, more than 900 astronomers from institutions affiliated with the telescope wrote an open letter calling on the astronomical community “to recognize the broader historical context of this conflict, and to denounce the criminalization of the protectors” on the mountain. The letter’s authors asked fellow astronomers to consider “the methods by which we are getting the telescope on the mountain in the first place.”

On October 7, 2014 Hawaiian cultural practitioners, environmentalists, and activists gather to stand in solidarity against the groundbreaking ceremony for the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT). #buildingTMT #aoleTMT. Image via Occupy Hilo/Flickr.

“Armed or not, the military and the police have become involved in the project’s deliberations with the protectors of Mauna Kea,” they wrote. The letter urged astronomers “to consider whether the future of our field is worth the damage to our relationship” to Native Hawaiians.

Today, while the future of the TMT is still hamstrung in Mauna Kea, supporters of Native Hawaiian struggles are pressuring the University of California, one of the observatory’s six funders, to pull out from the project. A petition urging UC to divest from the TMT project has been signed by 1,048 undergraduate students, 70 graduate students, 119 alumni and 266 UC staff and faculty, while an online petition has reached nearly 400,000 signatures.

There is no timeline set for construction, and the TMT is considering building in the Canary Islands instead.