Bristol Immigration Jail

In March 2020, immigrants who were facing deportation proceedings and locked up in the Bristol County House of Corrections — a jail in Massachusetts — were extremely concerned about contracting COVID-19 during the global pandemic.

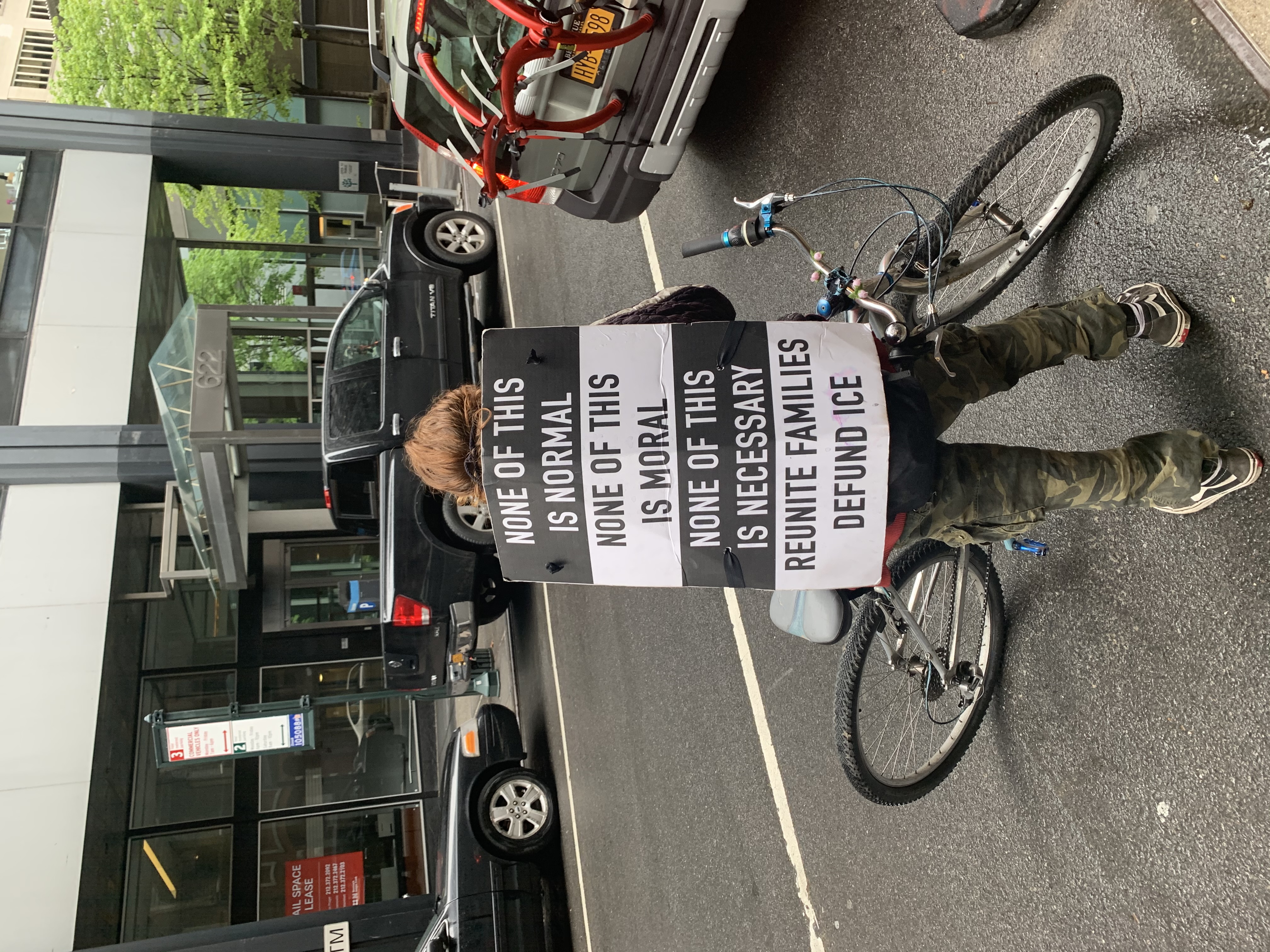

#FreeThemAll Car+Bike Demo in NYC: Say No To Death Camps. Car And Bike and Pedestrian Caravan Demanded Cuomo Release ICE Detainees During Covid-19 Pandemic, Plus Reduce Jail And Prison Populations. Image via Andrew Ratto/Flickr.

After they observed two corrections officers exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms, the people who were detained began to organize. Despite speaking different languages, people in one wing of the jail collectively drafted a letter describing the “overcrowded living conditions” that forced 57 people to share an area meant for ten, and “the reckless behavior” of the guards. In spite of the threat of retaliation from ICE and jail administrators, fifty-one incarcerated immigrants signed the letter, demanding release and/or bond hearings for those with serious medical conditions.

Fifty Bristol County immigrant detainees sent a letter to public officials over COVID-19 concerns

The letter from the immigrants mobilized groups on the outside, who were already organized to do short- and long-term work with people locked up. The Connecticut Immigrant Bail Fund, through its efforts to establish a pilot program that would guarantee legal representation to Connecticut residents in deportation proceedings and in immigration prison, had built relationships with attorneys who regularly visited detention centers in multiple New England states. It was one of these lawyers who was able to leak the immigrants’ letter, and then continue to liaise with the authors even after the jail staff and sheriff retaliated and locked down the facility. Similarly, the Boston Immigration Justice Accompaniment Network ran a hotline which was well known to people inside, and maintained communication with immigrants in spite of pandemic restrictions on in-person visits.

A grey station wagon is parked on the street. Words are painted across the windows in yellow: “#FREE THEM ALL. DON’T LET ICE CAMPS BECOME COVID DEATH CAMPS.” Image via Andrew Ratto/Flickr.

As attorneys across the country began filing habeas and class action lawsuits to free as many people as possible from immigration prisons, they relied on descriptions of conditions obtained from those organizing inside the Bristol County House of Corrections. Those testimonies were instrumental to winning a federal judge’s order, which released 50 people out of a total of 148 people in detention.

A dark blue car is parked on the side of the street. “EVERY CAGE IS A CRISIS” is written in white letters on a black sign, which is affixed to the hood of the car. Image via Andrew Ratto/Flickr.

This hard-won freedom came at a high cost. When inside organizers resisted being moved to another cell within the coronavirus-stricken facility, the Bristol County Sheriff and his deputies unleashed pepper spray, dogs, and riot gear to attack the unit where detainees had organized.

One terrified caller described the scene to Rev. Annie Gonzalez Milliken, a pastor with the Boston Immigration Justice Accompaniment Network: “The sheriff approached me violently, grabbed my arm and scratched me, police came with pepper spray, spraying in everyone’s face and spraying in my mouth, and I suffer asthma. And then they retreated, a lawyer was on the phone and he witnessed everything, they cut off all the phones except two are still working. They’re outside with the canine unit, bullet proof vests, and riot gear. The sheriff attacked me, he was out of his mind, I saw the devil in his eyes.”

Blurred lights of cars on a highway, photographed at a slow shutter speed. People stand on the overpass above the highway, holding lighted signs that spell out the words “ABOLISH ICE.” Image via Joe Brusky/Flickr.

Even after being released from detention by court order, immigrant leaders who organized behind bars continued to be targeted outside. ICE is aggressively pursuing those individuals, and trying to revoke their bail, rearrest or deport them.

One organizer, who was made to wear a GPS tracking device as part of his release conditions from the immigration prison in Bristol County, was given contradictory information from ICE’s ISAP program and the jail on whether he was on house arrest or allowed to go to work. He had his bail revoked and is now in immigration detention.

Image via United We Dream.

Still, the ongoing efforts from detained people continue to bring outside groups together, said Ana María Rivera-Forastieri from Connecticut Immigrant Bail Fund. “They’ve organized us so well,” she said. “We are going to start doing bi-weekly meetings with families of those released.”

Free Joan Little

The following is an excerpt from “Free Us All” by Mariame Kaba.

“Defense campaigns for criminalized survivors of violence like Bresha Meadows and Marissa Alexander are an important part of a larger abolitionist project. Some might suggest that it is a mistake to focus on freeing individuals when all prisons need to be dismantled. The problem with this argument is that it tends to render the people currently in prison as invisible, and thus disposable, while we are organizing towards an abolitionist future.

In fact, organizing popular support for prisoner releases is necessary work for abolition. Opportunities to free people from prison through popular support, without throwing other prisoners under the bus, should be seized.

Of course, defense campaigns are most effective as abolitionist strategies when they are framed in a way that speaks to the need to abolish prisons in general. The campaign cannot be framed by a message such as: “This is the one person who shouldn’t be in prison, but everyone else should be.” Rather, individual cases should be framed as emblematic of the conditions faced by thousands or millions who should also be free.

This video was conceived by Mariame Kaba and narrated by CeCe McDonald. Directed and produced by Dean Spade and Hope Dector. Audio editing by Lewis Wallace. Visual art by Micah Bazant. Created by the Barnard Center for Research on Women and Survived and Punished.

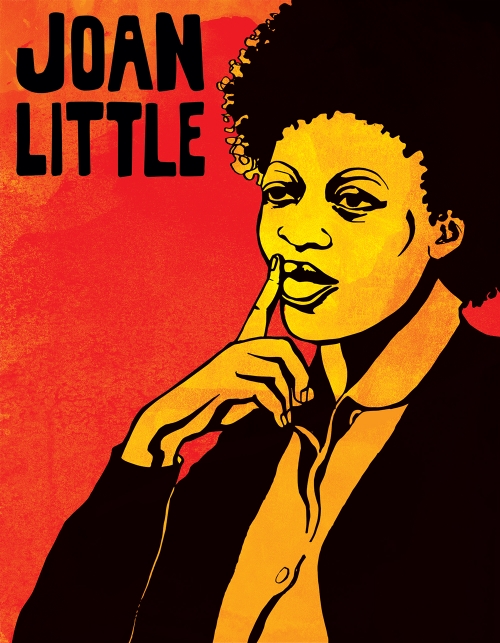

Both Marissa and Bresha’s freedom campaigns were inspired by the 1974 effort to free Joan Little, a 20-year-old Black woman prisoner. Defending herself against Clarence Allgood, a white guard who was sexually assaulting her, Joan Little grabbed an ice pick from his hand and stabbed him. Allgood died and Little escaped, eventually turning herself in to authorities a week later and claiming self-defense. She was charged with first-degree murder, which carried a possibility of the death penalty. Her plight soon inspired a mass defense campaign that became known as the “Free Joan Little Movement.” Organizations and individuals across the country raised money for her bond and her defense. When Little’s trial began on July 15th 1975, five hundred supporters rallied outside the Wake County Courthouse. According to historian Danielle McGuire’s At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance, the supporters “hoisted placards demanding the court ‘Free Joan Little’ and ‘Defend Black Womanhood,’ and loud chants could be heard over the din of traffic and conversation. ‘One, two, three. Joan must be set free!’ the crowd sang. ‘Four, five, six. Power to the ice pick!’”

Black and white drawing of Joan Little. Image via dignidadrebelde/Flickr.

Eventually, after a five-week trial and 78 minutes of deliberation, Joan Little was acquitted by a jury and returned to prison to serve time for her original offense, which was a break-in. The case is recognized as the first time a woman was acquitted of murder on the grounds of self-defense against rape. It continues to stand as a testament to Black women’s resistance to subjugation and sexual predation.

Portrait of Joan Little created for Project NIA’s exhibition “No Selves To Defend — 10 Women Criminalized For Defending Themselves.” Image via Micah Bizant.

The #FreeBresha and #FreeMarissaNow campaigns, like the Free Joan Little defense campaign that came before it, have taken great pains to underscore that each survivor is one among thousands of Black women and girls who have been and continue to be criminalized for trying to survive. The message now, as it was then, is that all of the Joans, Marissas, and Breshas should be free.“